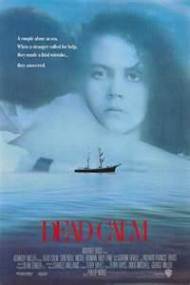

In the 1989 film, “Dead Calm” by Phillip Noyce with Nicole Kidman, Sam Neill and Billy Zane, a lone couple on a boat offers hospitality to a shipwreck victim, Hughie, who soon turns out to be a manic murderer. Here is a film review: “The main flaw in this otherwise excellent thriller movie is the first 15 minutes or so. The horrific traffic accident in which the sailing couple lose their only child adds nothing to the main line of the movie’s tale.” I agree about the excellence of the thriller, which is by the way Nicole Kidman’s first performance. I don’t agree with the death of their son having nothing to do with the story. Dick and I lost our Stuart over a year ago, and our similar storyline of a lone couple who has lost a son and goes on a boat trip, leads me to believe the film is all about the couple’s loss and how they deal with it. In this perspective, Hughie is an allegory of grief (“Grief”), and if you want to get an idea about how going through grief feels (and would like to see Kidman as a young actress), watch the movie.

Going through grief is just as violent as what the couple goes through. It takes your mind over but your body too, all the time, with no chance for escape. In the movie, John and Rae are quickly separated. No matter how close the couple, grief is an experience you live through on your own. John goes on the wrecked ship, where he encounters death face on. When losing a child, you worry about what happened to him, and you can’t put aside dealing with death as you might have done before. John almost dies suffocated, yet keeps on fighting through it. Living with grief requires that type of endurance. If you choose to live, you must walk through the fire day after day before you can make it to the other side.

Meanwhile, Rae is physically violated by Grief (Hughie rapes her). When you carried a baby for nine months, nursed him, felt his warm body as part of you (true for dads too), it is a violation in the most intimate part of your body when that child dies. Rae reacts little as she gets raped: the true violation came before, when her son died. She “just” relives the trauma.

John and Rae reach out for each other’s hand and are reunited. He washes her hair with a love of a new, deeper kind. Love that survives Grief is enlarged in the process–love for the child you lost that had to be transformed to reach him on the other side, but also love for your spouse, love for your other children (and their wives…), and yes, love for the world at large. And as we think John and Rae have won the battle, Grief comes back in another assault. You never get over Grief, but with time and like this couple, you get better at dealing with it.

What a beautifully and painfully perceptive reading of the film. The author and/or director must have meant to express a similar loss. The reviewer is certainly not a parent and completely missed the point.

Thanks, Holly. Reading you lately has reminded me of the wonderful time we had in our shared office. I actually dreamt I was going back to work!

Wow! Beautifully said — as usual. You continue to amaze me with your strength and your writing!

Sail on!